Letter from India: Service with a smile brightens India trains

NEW DELHI A few minutes after the Lucknow-bound express leaves Delhi, men in black suits, bow ties and baseball caps walk through the executive-class rail car, press their hands together in greeting, and - with theatrical politeness bordering on sycophancy - bow down to present every passenger with a red rose, wrapped in cellophane.

It is a gesture which leaves the passengers perplexed. No one can decide what to do with the flowers, most of which end up stuffed under the arm- rest.

The roses are the opening gambit in an all-out assault of hospitality on the first-class traveler. A few minutes later, individual thermos flasks are distributed at every seat, damp towels are offered to help wipe away the grime of the station, newspapers in Hindi and English appear, individual packets of cornflakes come on a tray with milk, snacks of potato-and- cashew cutlets follow, bananas are offered from a wicker basket, fresh fruit juice is poured.

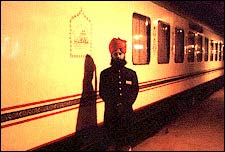

Hardly half an hour passes and men in starched scarlet turbans arrive to serve tomato soup with Italian bread sticks, bringing more white towels - this time to lay across your lap so splashes of soup do not soil your business attire.

A sign informs travelers that the new cushioned seats have "ergonomically designed backs, allowing excellent comfort without getting tired even on long journeys."

This elite service is far removed from the experience of most of the 15 million people who use Indian trains every day, but the idiosyncratic Indian railroad minister, Lalu Prasad, is eager to give the top end of the train network a radical makeover to win back the loyalty of the business travelers.

The railroad system is losing its first-class passengers to the new low- cost airlines that are aggressively promoting travel on routes traditionally served by trains. Although these rich train travelers represent just a tiny proportion of the total daily traffic, the fares generated by the air-conditioned rail cars have traditionally been used to subsidize the tickets of the third-class passenger and the disappearance of this revenue is a blow.

Lalu, as he is known, has decided to fight back. The features of the Delhi- Lucknow Shatabdi express are soon to be replicated in other executive rail cars throughout the system.

Lalu recently announced "that the year 2006 shall be the year of passenger service with a smile" - causing wry amusement among veteran travelers, who are unaccustomed to much passenger service or smiling on the railroads.

He knows that he has a stiff battle ahead. Only a few months ago he made the mistake of returning by train from his constituency in Bihar, eastern India, and declared after the trip: "My God, it was hellish."

"The toilet was so dirty that I can still feel the stench. I did not have my dinner. It was so nauseating," he was quoted as saying by Indian newspapers. "I will take some action."

So far, the action taken has been primarily targeted at improving things for the elite travelers.

With 1.5 million employees, the Indian railroad network is so vast that it has its own ministry within the government and its own annual budget. In a budget speech given at the end of last month, Lalu reduced the cost of the air-conditioned seats by 18 percent, pledged that tickets would soon be available through the Internet for all major trains, stressed the need for a "beautification" of train stations and promised that "modern facilities," such as ATMs and cyber cafés, would be provided "at all major stations speedily." There would also be a computerized feedback analysis of cleanliness standards.

In a separate announcement, he asked managers to make sure that cockroaches were not allowed to thrive in first-class rail cars.

How swiftly these changes will be introduced is a matter for debate. In any case, this was a curiously non- populist gesture for a politician whose most notable other railroad innovation to date was to ban the sale of Western-brand fizzy drinks in order to promote the sale of locally made buttermilk and Mango Frootis, a popular Indian drink.

"There has been an attitudinal shift in the railways," said Chetan Ahya, an economist with Morgan Stanley. "They are trying to respond to market needs, but there is no denying the fact that the government of India is not able to invest in infrastructure in the way that China is."

Ahya recently co-wrote a report highlighting how dramatically Indian railroad investment has fallen behind that of China over the past 15 years. Between 1990 and 2004, the Chinese railroad network grew by 29 per cent with 16,608 kilometers, or 10,300 miles, of track laid, but the Indian system expanded by only 1 percent, or 633 kilometers.

"You can keep making these small changes, but that is not going to solve the massive infrastructure deficit which the country has," he said.

Lalu will have to keep working on the service with a smile theme if he is to seduce passengers away from the slick new air services.

The suspension ride on this Shatabdi express is positively bone-rattling and no amount of on-board cosseting can remove the lingering horror of the predawn Delhi railroad station, with its rats, and heaps of sleeping bodies shrouded in blankets, its rancid sewage smells and its relentless flow of passengers and hustling porters, with towers of suitcases balanced unconvincingly on their heads.

There are still elements of first- class train travel not conducive to total relaxation. Several armed bodyguards, traveling with provincial VIPs, doze over their guns at the back of the rail car, rising occasionally to parade their weapons down the aisle.

Toward the end of the journey - delayed by two hours because of "mist" - the waiter service slows down and trails off entirely. A badged supervisor in pinstripes arrives to holler at the attendants, who have locked themselves in a box-like cubicle in the corridor and are sleeping on the floor.

Glimpses of the general discomfort of old-style Indian rail travel flash past outside the icily air-conditioned rail car, where weary faces are visible, crowded together and pressed up against the barred windows of trains moving slowly in the other direction.

"This is very interesting," said Kalyan Ghosh, an Indian businessman now based in London, fingering his rose. "You can't imagine how awful it used to be - the stench, the filth."

But he was conscious of traveling in a tiny bubble of modernity: "Things in this compartment are fine, but they're not so good in the rest of the train." This was a mirror of broader changes in India, he said. "One carriage benefits; the rest don't."

- Amelia Gentleman, International Herald Tribune

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home