A Letter From Dr. Pervez Hoodbhoy

(A slightly dated article, but nevertheless one of my perennial favourites)

Below is a thought-provoking report by Dr. Pervez Hoodbhoy of his impressions of India, while there on a month-long lecture tour, in connection with his UNESCO’s Kalinga Prize in 2003.

Dear Friends,

A full four weeks ago I began my UNESCO 2003 Kalinga Prize visit to India. Although delayed, improved Pakistan-India relations eventually made this possible. It has been a relentless schedule from day one, with 2, 3, 4 lectures every day at schools, colleges, universities, research institutions, and NGOs. This trip has taken me all around India: Delhi, Pune, Mumbai, Bangalore, Chennai, Hyderabad, Bhubhaneswar, Cuttack, Calcutta, and finally back here in Delhi again. This has been an extraordinary visit. I interacted with children from excellent schools as well as those from pretty ordinary ones; had long sessions with students and teachers from colleges and universities; met with the "junta" (cooks, taxi drivers, and rickshawallas); and was invited to see ministers and chief ministers in several states, as well as the president of India. This extended tour of the so-called "enemy country" has been an enormous learning experience for me. I am not aware of any Indian who has made a similar kind of journey to academic institutions in Pakistan.

The events of the last four weeks could really fill a book. Let me instead quickly record a few of my observations and experiences that you might find interesting.

• Many Indian universities have a cosmopolitan character. Their social culture is modern and similar to that in universities located in free societies across the world. (In Pakistan, AKU and LUMS would be the closest approximations.) Male and female students freely intermingle, library and laboratory facilities are good, seminars and colloquia are frequent, and the faculty is intensively engaged in research. Entrance exams are tough and competition for grades is intense. The research institutes I visited (TIFR, IISC, the IIT's, IMSc, IICT, IUCAA, JNCASR, Raman Institute, Swaminathan Institute,.....) are world class.

• The rural-urban divide in India is strong. Schools and colleges in small towns have a culture steeped in religion. Here one sees hierarchy, obedience, and even servility. The national anthem is sung in schools and religious symbols are given much prominence. Some students I met were bright, but many appeared rather dull. Although most Indian colleges are coeducational (unlike in Pakistan where only some are), male and female students sit separately and are not encouraged to intermingle. It is sometimes difficult to understand the English spoken there. Where possible, I spoke in Hindi/Urdu. This enhanced my ability to communicate and also created a special kind of bonding. There is an evident desire to improve, however, and at least some college principals go out of their way to organize events and invite guest speakers. My lecture at the Basavanagudi National College, a fairly ordinary college, was the 1978th lecture over a period of 30 years!

• Independent thought in India's better universities is alive and well. Office bearers of the Jawaharlal Nehru University students union in Delhi were requested by the university's administration to present flowers to President Abdul Kalam at the annual convocation. They flatly refused, saying that he is a nuclear hawk and an appointee of a fundamentalist party. Moreover, as young women of dignity they could not agree to act as mere flower girls presenting bouquets to a man. Eventually the head of the physics department, also a woman, somewhat reluctantly presented flowers to Dr. Kalam but said that she was doing so as a scientist honoring another scientist, not because she was a woman. Bravo! I have not seen comparable boldness and intellectual courage in Pakistani students. Student unions in Pakistan have been banned for two decades and so it is a moot question if any union there could have mustered similar independence of thought.

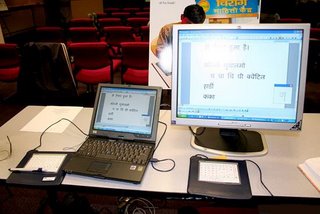

• Taking science to the masses has become a kind of mantra all over India. My columnist friend Praful Bidwai - a powerful critic of the Indian state and its militaristic policies - counts among India's greatest achievements the energisation of its democracy and refers to "our social movements, with their rich traditions of people's self-organisation, innovative protest and daring questioning of power". These movements have ensured that, unlike in Pakistan, land grabbers in Indian cities have found fierce resistance when they try to gobble up public spaces - parks, zoos, playgrounds, historical sites, etc. Praful should also include in his list the huge number of science popularization movements, sometimes supported by the state but often spontaneous. These are sweeping through India's towns and villages, seeking to bring about an understanding of natural phenomena, teach simple health care, and introduce technology appropriate to a rural environment. There is not even one comparable Pakistani counterpart. I watched some science communicators, such as Arvind Gupta at IUCAA in Pune, whose infectious enthusiasm leaves children thrilled and desirous of pursuing careers in science. Individual Indian states have funded and created numerous impressive planetariums and science museums, and local organizations are putting out a huge volume of written and audio-visual science materials in the local languages.

• Attitudes of Indian scientists towards science are conservative. Progress through science is an immensely popular notion in India, stressed both by past and present leaders. But what is science understood to be? I was a little jolted upon reading Nehru's words, written in stone at the entrance to the Jawaharlal Nehru Institute for Advanced Research in Bangalore: "I too have worshipped at the shrine of scienc". The notion of "worship" and "shrine of science" do not go well with the modern science and the scientific temper. Science is about challenging - not worshipping. But science in India is largely seen as an instrument that enhances productive capabilities, and not as a transformational tool for producing an informed, rational society. Most Indian scientists are techno-nationalists - they put their science at the service of the state rather than the people. In this respect, Pakistan is no different.

• India's nuclear and space programs are nationally venerated as symbols of high achievement. This led to India's nuclear hero, Dr. Abdul Kalam, becoming the country's president. When Dr. Kalam received me in his office, after the usual pleasantries, I expressed my regret at India having gone nuclear and causing Pakistan to follow suit. Shouldn't India now reduce dangers by initiating a process of nuclear disarmament? Dr. Kalam gave me a well-practiced response: India would get rid of its nuclear weapons the very minute that America agreed to do the same. He displayed little enthusiasm for an agreement to cut off fissile material production. However, he did agree to my suggestion that exchange of academics could be an important way to build good relations between

Pakistan and India.

• Indian society remains deeply superstitious, caste divisions are important, and women still have a long way to go. While I found myself admiring the energetic popular science movements, I was disappointed that they pay relatively little attention to anti-scientific superstitions that pervade Indian society. The jyoti[sh] (astrologer) dictates the dates when a marriage is possible, and even whether a couple can marry at all. After I gave a strong pitch for fighting superstition, a young woman asked me what to do if "koi devi aap pay utr jayai" (if a spirit should descend upon you). Inter-caste marriages are still frowned upon, and usually forbidden. In local newspapers one typically reads of tragic accounts such as that of a boy and girl from different castes who commit suicide together after their families forbid the match. Although Indian women are freer, more visible, and more confident than their Pakistani counterparts, India is still a strongly male dominated society. However, the rapidly increasing number of well-educated young women gives hope for the future.

• Muslims in India remain at the margins of scientific research and higher education. Hamdard University in Delhi is distinctly better than the university bearing the same name on the Pakistani side. Jamia Millia, a largely Muslim university, appears to be doing well and a bit better than any Pakistani university in the field of physics. But, although Muslims form 12% of India's population, I met only a few Muslim scientists in leading Indian research institutes and universities. Discrimination against Muslims does not appear to be the dominant cause. A professor at Jamia told me that an overwhelming number of Muslim students were inclined towards seeking easier (and more lucrative) professions in spite of special incentives offered to them at his university. In general, Muslims in India appear more modern and secular than in Pakistan. However, Hyderabad surprised me. In the lecture that I gave at a government women's college, there was only one young woman without a burqa in an audience of about a hundred. The women there were astonished to learn that Pakistan is, at least in most places, more liberal than Hyderabad. The extreme conservatism in the Muslim part of Hyderabad city reminds one of Peshawar.

• There was a remarkable lack of hostility towards Pakistan. Indeed a desire for friendly relations was repeatedly expressed in every forum I went to. This is not to be taken lightly: many of my public lectures were either about (or on) science, but others dealt with deeply contentious issues - nuclear weapons, India-Pakistan relations, and the Kashmir conflict. Various Indian peace groups and NGOs organized public discussions and screenings of the two documentaries that I had made (with Zia Mian): "Pakistan and India under the Nuclear Shadow", and "Crossing the Lines - Kashmir, Pakistan, India". To be sure, my views on Indian policies and actions in Kashmir occasionally provoked knee-jerk nationalistic responses, but these were infrequent and exchanges always remained within the bounds of civility.

• Ignorance about Pakistan is widespread. In most public gatherings, and certainly in every school that I spoke at, people had never seen a Pakistani. Many Indians have a misconception of Pakistan as a medieval, theocratic state. In fact, only some parts of Pakistan can be so characterized. Many Indians think that Pakistanis have been totally muzzled and live in a police state. This is also untrue - articles in the Pakistani press are often blunter and more critical than in the Indian press. An Indian friend hypothesized that knowledge of the other country is inversely proportional to the geographical distance between countries. Unfortunately this will remain true unless there is a substantial exchange of visitors between the two countries.

• Indians are deeply nationalistic and may dislike particular governments but they only rarely criticize the Indian state. This is easy to understand: the democratic process has given a strong sense of participation to most citizens and successfully forged an Indian national identity (except in Kashmir, and parts of the North East) that transcends the immense diversity of cultures across the country. But this has an important downside: nationalism is easy to mobilize and highly dangerous in matters of war and conflict. I found the smugness of the Indian elite (especially the heads of nuclear, space, and technology programs) to be rather irritating. Even if India has done well in some respects, in most others it is still behind the rest of the world. Fortunately, Pakistani intellectuals are less attached to their state and therefore more forthright. The reason is rather clear: three decades of military rule have dealt a serious blow to nation building and firming up the Pakistani identity.

• Similarities between the two countries exceed the differences. Cities in both countries are poisoned with thick car fumes (Delhi is the exception) and grid-locks are frequent; megaslums and exploding populations threaten to swallow up the countryside; electricity supplies are intermittent; and water is fast disappearing from rivers and aquifers. The rural poor are fleeing to the cities, and wretched beggars with amputated limbs are casually accepted as part of the urban scenery. The absence of long-term planning is manifest. Obsessive militarization and reckless spending on defense shows no sign of abating in either country.

So much for all that.

As I head back home to Islamabad, I want to thank the many friends and organizations in India who made elaborate logistical travel and accommodation arrangements for my wife Hajra and myself. Others arranged my talks and public meetings, sometimes on subjects normally considered as deeply controversial and divisive. They worked hard to make each event a success. This letter is also addressed to those who I met for the first time but who I would like to keep in contact with. It would take much too long to write to scores of people individually, and so I ask for forgiveness in sending this one letter to all.

With best regards,

Pervez Hoodbhoy

Dr. Hoodbhoy received Ph.D in nuclear physics from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and has been a faculty member at the Department of Physics, Quaid-e-Azam University, Islamabad since 1973. Besides making the two widely acclaimed documentaries ("Pakistan and India under the Nuclear Shadow", and "Crossing the Lines - Kashmir, Pakistan, India"), he has authored a number of publications and lectured widely to promote science education, better environmental policies, women's rights and education.